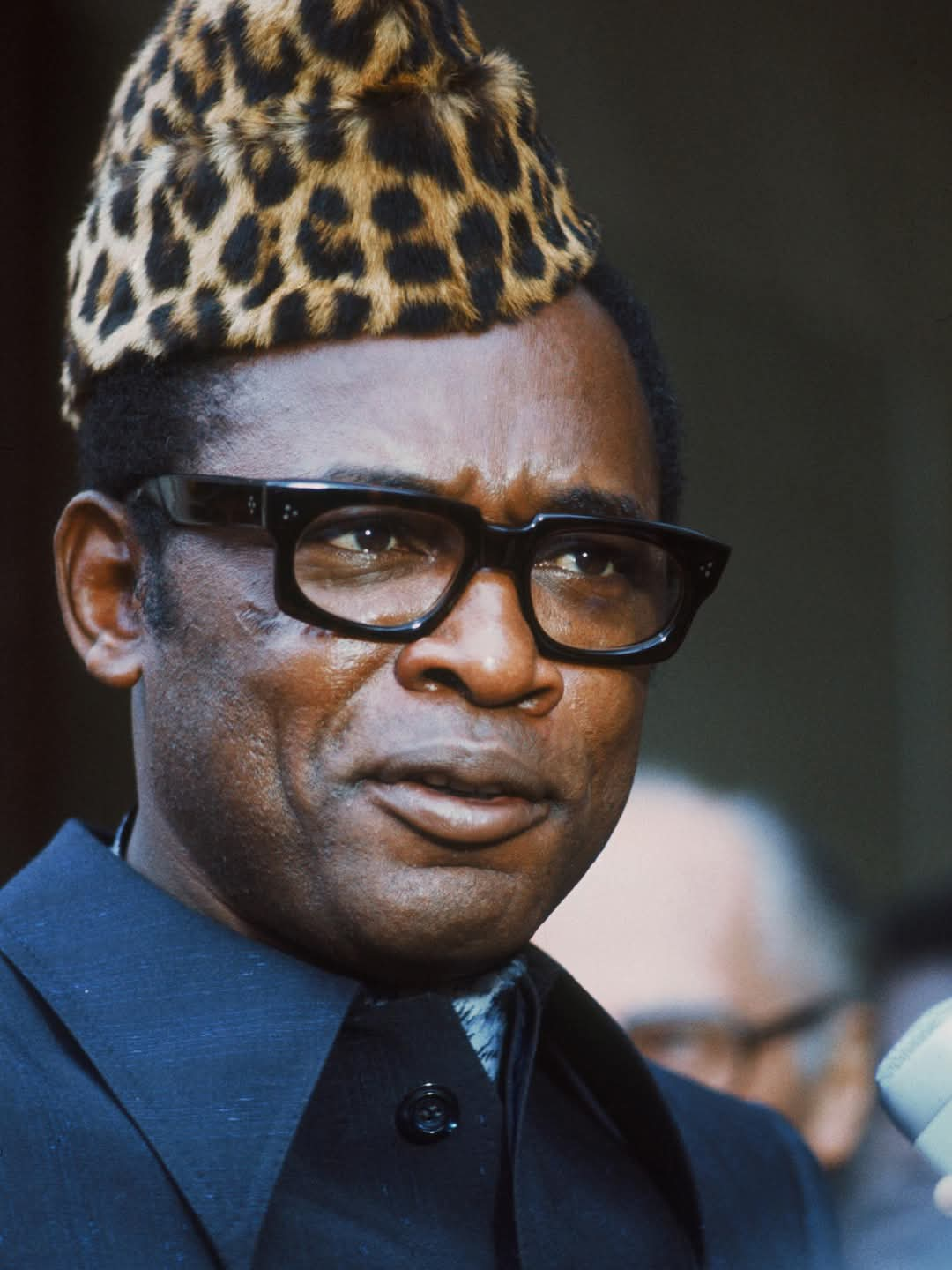

Mobutu Sese Seko: The Rise and Fall of Zaire’s Longtime Ruler Early Life and Military Career

Zaharaddeen Ishaq Abubakar | Katsina Times

Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, later known as Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa Za Banga, was born on October 14, 1930, in Lisala, northern Congo (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). After his father’s death, he was raised by his mother and later joined the Force Publique, the colonial army of Belgium, where he rose to the rank of Sergeant.

Following Congo’s independence in 1960, he was appointed Chief of Staff of the army, a position that paved the way for his entry into national politics.

Political Ascent and Coup d'État

After independence, Congo was engulfed in political turmoil between Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba and President Joseph Kasavubu. On September 14, 1960, Mobutu led a coup with the backing of Belgium and the United States, removing Lumumba from power. Lumumba was later arrested and executed in 1961.

In 1965, Mobutu staged another coup, ousting President Kasavubu and consolidating his power as the country’s supreme leader.

Authoritarian Rule and Political Reforms

Upon taking control, Mobutu adopted two key policies:

- Repression of Opposition – He banned multi-party politics and established a one-party state under the Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution (MPR).

- Cultural Authenticity ("Authenticité") – In 1971, he renamed the country Zaire and mandated the abandonment of European names in favor of African identities.

Despite these initiatives, his regime became notorious for corruption and autocracy. He amassed vast personal wealth, with estimates suggesting he embezzled over $5 billion from state funds.

Global Perception: Support and Criticism

- Western Backing – During the Cold War, Mobutu was a strategic ally of the United States and France, receiving military and financial aid in exchange for opposing communism.

- Domestic Discontent – Inside Zaire, his rule was marked by economic decline, human rights abuses, and widespread dissatisfaction. By the late 1980s, public unrest grew due to economic hardship and unpaid wages.

Downfall and Exile

By the 1990s, Mobutu’s grip on power weakened. In 1997, a rebellion led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, with support from Rwanda and Uganda, overran the country.

As rebel forces advanced on Kinshasa, Mobutu fled, first to Togo and later to Morocco, where he died of cancer on September 7, 1997.

Legacy and Historical Reflection

Mobutu's rule showcased the challenges of post-colonial African leadership, where Western-backed strongmen often prioritized personal power over national development. His fall serves as a cautionary tale on the consequences of authoritarianism, corruption, and economic mismanagement.

Today, his legacy remains a stark reminder of the fragile balance between power and accountability in governance.