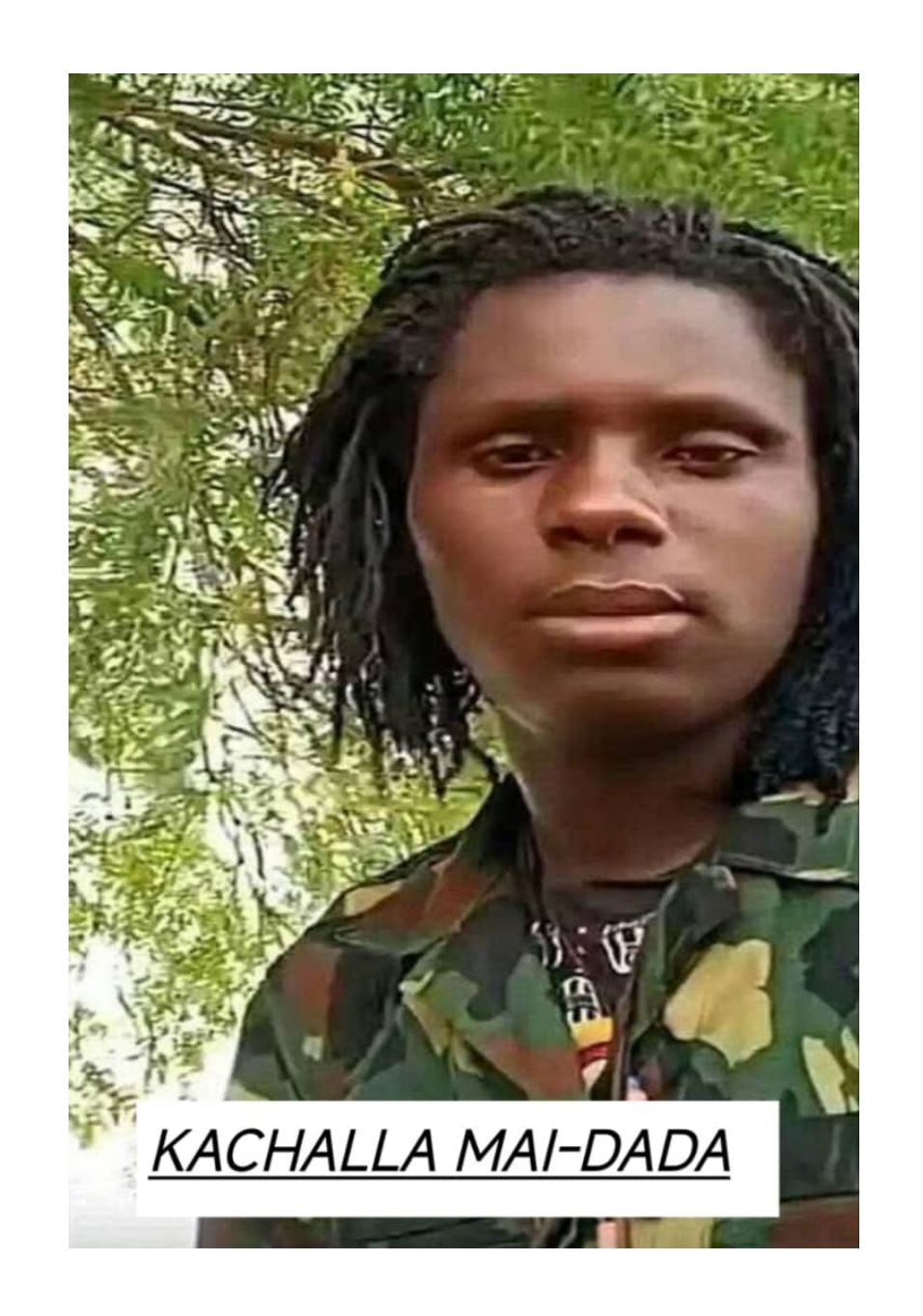

The Fall of a Tuareg Bandit Kingpin: The Death of Mai-Dada in Zamfara State

By Dr. Murtala Ahmed Rufa’i

Associate Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies,

Department of History & International Studies,

Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto

Background

The killing of the notorious Tuareg bandit leader, Kachalla Saminu—popularly known as Mai-Dada—is expected to bring much-needed relief to residents of Mayanchi, Maru, Maradun, Talata Mafara, Tureta, and Bakura, as well as commuters and quarry workers along the Gusau–Sokoto highway.

Following his death, more than 120 disillusioned members of his militia—including fighters from the infamous Na’ika bandit network in Maradun Local Government Area (LGA)—have approached local communities to initiate dialogue and explore opportunities for reintegration.

Mai-Dada was a dominant and feared figure in the criminal landscape of northwestern Nigeria, implicated in widespread acts of kidnapping, cattle rustling, illegal gold mining, and the dissemination of violent propaganda through social media. He was linked to the deaths of countless vigilantes and security operatives, the displacement of entire villages, and the extortion of over ₦150 million in protection levies—often targeting foreign nationals, particularly Chinese and Lebanese workers employed at quarry sites along the highway.

Early Life and Background

Born as Kachalla Saminu, Mai-Dada earned his nickname due to his signature dreadlocks. He was also known as Mai Jikka. He was associated with more than 250 armed groups connected to the Na’ika bandit family in Maradun LGA, Zamfara State. Despite his vast criminal influence, he was only 27 years old at the time of his death.

His parents, believed to be of Tuareg origin, had migrated from the Tahoua region of Niger Republic and eventually settled in Balde village near Mayanchi in present-day Maru LGA. He was mentored by notorious Tuareg bandit leaders, including Amadu, Saidu, Lawali, and Jemo Smally—all key players in the violent Na’ika network. He was killed during a confrontation with local vigilantes on 25 June 2025, leaving behind a wife and two children.

Areas of Operation

Mai-Dada launched his criminal career in the vicinity of the Bakalori Dam in Maradun, taking advantage of the region’s difficult terrain to avoid security detection. Like other gangs operating in the Bayan-Ruwa area, he amassed significant wealth through banditry and illegal gold mining. The proceeds were used to procure sophisticated weapons and further consolidate his influence.

After establishing a base along the Bakura–Talata Mafara axis of the Gusau–Sokoto highway, he coordinated a series of violent attacks on communities across Zamfara and parts of neighboring Sokoto State. Affected villages included Tatala Mafara, Bakura, Maradun, Maru, Gidan-Kano, Danbaza, Kadauri, and Garagi in Zamfara, as well as parts of Tureta LGA in Sokoto.

He built strategic alliances with other prominent warlords such as Jemo Smally, Saidu Na’ika, Amadu, Kachalla Dansadi, and Kachalla Haru, thereby expanding his operational reach across the region.

Notorious Crimes and Human Rights Violations

Mai-Dada became infamous for his systematic targeting of travelers and government officials. He operated with brutality along key routes like Kuka Mai Rahu, Kwanar Sado, Kadauri, and Gidan Kano. In early 2024, he abducted a senior engineer with Triacta Construction Company near Kuka Mai Rahu. In April that same year, he murdered Umar Dan Asabe, the Director of Health for Talata Mafara LGA.

He used social media platforms—particularly TikTok—to promote his violent ideology and boast about his crimes. In some videos, he claimed responsibility for killing security personnel and openly admitted to extorting protection money from companies.

He frequently blocked the Funtua–Tsafe highway, armed with automatic rifles and explosives. Witnesses reported horrifying accounts of passengers being separated by ethnicity—Hausa victims were often executed on the spot, while Fulani passengers were spared and even assisted financially.

In one shocking episode, he reportedly amputated a man from Tsafe with an axe. His violent tactics and anti-Hausa rhetoric earned him the moniker "Shekau of Zamfara." Despite being in his early twenties, he commanded a militia of at least 120 fighters and consistently flaunted his weapons and illicit wealth on social media.

His reign of terror was so severe that families in vulnerable villages would send their daughters away at night to avoid abduction or sexual violence.

Death of a Warlord

On the afternoon of 25 June 2025, at around 3:00 p.m., a gun battle erupted on the outskirts of Garajin Mayanchi and Ruheni in Maru LGA. Mai-Dada and a small group of armed men riding motorcycles attempted to ambush local vigilantes. However, acting on credible intelligence, the vigilantes launched a pre-emptive counter-ambush.

A fierce exchange of gunfire followed, resulting in the deaths of Mai-Dada and six of his fighters. After the battle, vigilante groups from Garagi, Kadauri, Mayanchi, and surrounding areas mutilated his corpse with machetes. Graphic images of his body quickly spread across social media platforms, sparking fears of possible revenge attacks from his surviving allies.

This encounter marked the third attempt on his life by the same vigilante coalition, having failed to neutralize him in two earlier operations.

The death of Mai-Dada marks a significant tactical victory for local vigilantes and affected communities in Zamfara State. However, it also highlights the persistent fragility of peace in Nigeria’s northwestern region.

The gruesome treatment of his body may provoke retaliatory violence from allied bandit groups. Moreover, the underlying causes of banditry—such as poverty, youth unemployment, illegal mining, ethnic tensions, and weak state presence—remain unresolved.

Therefore, while the elimination of Mai-Dada provides temporary relief, long-term peace and security will require a sustained, multi-pronged strategy. This should include not only military action but also social reintegration programs, regulation of resource exploitation, and community-based conflict resolution mechanisms across Zamfara, Sokoto, and neighbouring states.