Latest News

The Ethnographic Novel – Bature Tanimu Gagare’s Greatest Contribution to Hausa Literature and Historical Ethnography

By Professor Abdallah Uba Adamu

Bature Tanimu Gagare’s ethnographic novel is the first that I know in the Hausa language that provides a critical perceptive on the Maguzawa. But, let’s pause here.

This term is now clearly arrogant, pejorative and sneering, reference for the Hausa in the “us” and “they” cultural universe that separates the Hausa from anyone else. It is rooted in Cancel Culture. So, why not re-route it? Let’s use “Asalan”, or when a qualifier is needed, “Hausa Asalan.” I could use the real Hausa word, “Gangariya”, but it sounds less academic, ko ba haka ba? Plus it doesn’t really capture “original”, just “qualitative.” If I may be pedantic, it actually means “a well-formed, well-developed girl” (yarinya gangariya, watau mai kafasiti). Since “Majus” (fie-worshipper or simply a pagan) is Arabic and gave the root phrase Maguzawa, let’s go back to the Arabic and substitute with a better reference, “Asalan” (originally).

Habe, meaning “indigenous”(although it is not clear whether the Pulaar in Futa Tooro will accept if Hausa migrants refer to them as Habe, since that is their indigenous root) somehow transformed into Maguzawa through religious, not linguistic relationship and is clearly derogatory, as it refers to them being pagans. True, just like in many ethnic groups, there are many that are pagan – following alternative religious belief, and had been doing that for hundreds of years.

The religious wars and ethnic cleansings over the centuries have changed nothing. Yet the term is used as a general label for ALL who self-identify as Hausa, regardless of piety. For instance, the first Jihad in the Sahel was by Sultan of Kano Ali (1349-1385, who continued the fight from his father. Subsequently, eight of the Sultans of Kano before 1805 were called “Muhammad” including the greatest of them all, Muhammad Rumfa (1463-1499).

Specifically, the label is gleefully used by Fulani historians to refer to all pre-Fulani Hausa rulers – regardless of how pious they were or their contributions to Islam. Sadly, the Hausa historians themselves (e.g. in The Chronicle of Abuja), use the term, but only to indicate indigeneity, not lack of religion or monotheistic religion; for Abuja was founded by Muslim rulers). So, from this point onward, I will be using the expression “Hausa Asalan” for the group previously referred to as Maguzawa. And their lives as “Asalanci.” Incidentally, Iranians were once also referred to as Magi (Maguzawa) due to their ancient religion, Zoroastrianism.

The most comprehensive information about Bature Gagare and his novel was the interview by the ace journalist with the nose of the unusual, Ibrahim Sheme. This was held on 5th August 2001, and published in Weekly Trust on 17th August of the same year. A copy used to exist on Gumel.com, but somehow it has disappeared. I am not sure if Ibrahim Sheme has a copy of the interview in his Bahaushe Mai Ban Haushi blogspot.

The only researchers who noted the interview for its significance and historical value were Graham Furniss (1998) then at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, and Stanisław Piłaszewicz (2015) of the University of Warsaw, Poland. Prof Piłaszewicz (no, I can’t pronounce it either, so relax, you are in good company) has also supervised an M.A. thesis titled (from the translation) “The image of the religious life of Maguzawa in the novel Ƙarshen Alewa Ƙasa by Bature Gagare.”

However, wane tudu, wane gangare, I was able to fish out a copy of the interview in my archives! This is useful as it helps explain the book and the author’s intentions in writing the novel. For instance, Bature says of himself:

“I am basically intuitive when it comes to putting the first word on a paper. I have no rules, no plans, no inhibitions of any sort. Words just flow with rapidity so intense that I find it hard sometimes to keep up with my pen. Ideas mutate, the novel forms, characters emerge from naught. Sometimes I could not even predict what would happen next. In fact that was what happened when I was writing Karshen Alewa Kasa. The book just emerged from my scribbles.”

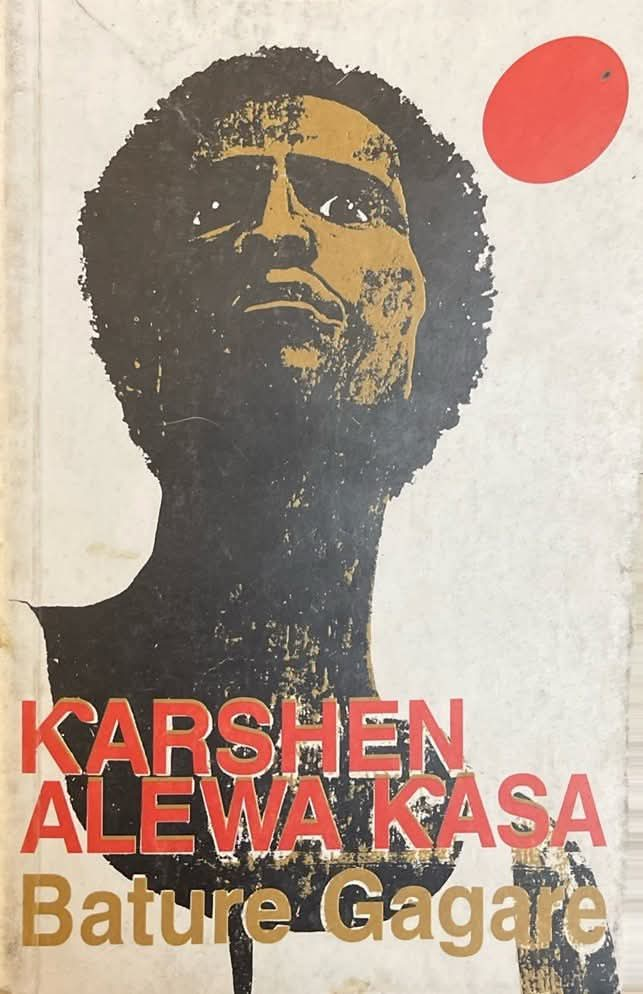

Karshen Alewa Kasa, the product of a literary completion was published by the then Federal Ministry of Culture in 1982, after it had won third place in a writing competition organized by the ministry in 1980. At that time, the 342-page book was the lengthiest novel published in the Hausa language. This record was later broken by first Rahma Abdul Majid’s “Mace Mutum” (2011) at over 520 and Fatima El-Ladan’s “Muma ƳaƳa Ne (2023) at 644 pages. It was also the first real modern thriller in Hausa. It tells the story of Mailoma, a Hausa pagan who acquired expensive tastes and a ruthless criminal bent in Kano and Lagos cities and then returns to his rustic, backward village somewhere near Kano where he leads a criminal gang into a volatile, deadly megalomaniac project.

The novel is composed of eleven chapters and can be divided in two thematic parts. The first two chapters present an idyllic life in a Hausa Asalan village Tsaunin Gwano [The Hill of Stink-Ant]. In a vivid and conversational style the Gagare depicts the local customs, organisation of the villagers, their occupations, and especially their ancient magical and religious beliefs. In that village Mailoma (alias Ƙanzunzum, alias Maguzi), the main character of the novel, was born. Having experienced different life vicissitudes, he decides to create a terrorist organisation and manages to make his plans real. His actions change the character of a story making it more sensational.

So, why did he pick Hausa Asalan people as the theme of his novel? His answer in the interview with Ibrahim Sheme is truly revealing and to me, laid down the basis of Hausa Wokeist Revival, long before the word ‘woke’ became part of the mainstream identity marker. Here is his rationale:

“I picked on the Maguzawa clan as the subject matter of the novel because even as early as the eighties, I was highlighting the society about the dangers of marginalization. The Maguzawa as you know is a derogative term, coined by the Hausa-Fulanis to identify the unconquered group of Hausa speaking peoples among them. The Maguzawa had been the victims of Muslim Hausa-Fulani domination and segregation for over one hundred years because, although Hausas themselves, they had held tenaciously to animistic practices. All attempts to Islamise them by the Jihadists or Christianise them by the missionaries had not eliminated this proud race. For this reason, the Maguzawa are barely tolerated among the Hausa-Fulanis. They are marginalized and isolated, derided and shunned. They are second-class citizens, denied education, employment and social recognition. The Maguzawa are a raw material that can be moulded by any evil genius for the purpose of revolt, insurrection or organised crime. The principal character in Karshen Alewa Kasa, Mailoma, opted for crime.”

Thankfully, this nightmare scenario did not play itself out. Ƙarshen Alewa Ƙasa is a Hausa Wokeists Manifesto, declaring unflinching support, identity, and recognition of a marginalized group to whom the Hausa owe their language.

A downside, though. One thing that irks me whenever I lay my eyes on the cover of Karshen Alewa Kasa is the artwork. The crazy eyes of the male figure with disheveled hair are a grotesque representation of Mailoma. Who says just because he is Hausa Asalan, he must look wild, crazy and disheveled? I know Bature had no hand in the artwork as it was done by the Ministry of Culture’s Art Department. But I have a feeling they deliberate chose d a stylized “Bamaguje” in tune with their image of the “original Hausa”. I think it is insulting.

Gagare’s fieldwork was one of the most impressive immersive methodologies that went beyond the surface, and in the final analysis, produced a master narrative. Allah Ya jikan shi da gafara.

If you want to read an academic treatment of Bature Gagare’s novel, the article by Stanisław Piłaszewicz is a good source. Note, though, Prof Piłaszewicz never met Bature, and he composed the article mainly from the classic interview Ibrahim Sheme held with Bature Gagare published in the Weekly Trust (Aug. 17, 2001), .

Piłaszewicz, Stanisław. 2015. “Bature Tanimu Gagare: Hausa Social Activist and Writer.” Studies of the Department of African Languages and Cultures (University of Warsaw) 49: 53-67. You need to download it quickly enough. If the link becomes broken or missing, there is nothing I can do about it. Acibilistically available at https://bit.ly/4kuVBkX.